Antelops Horns not just for show.

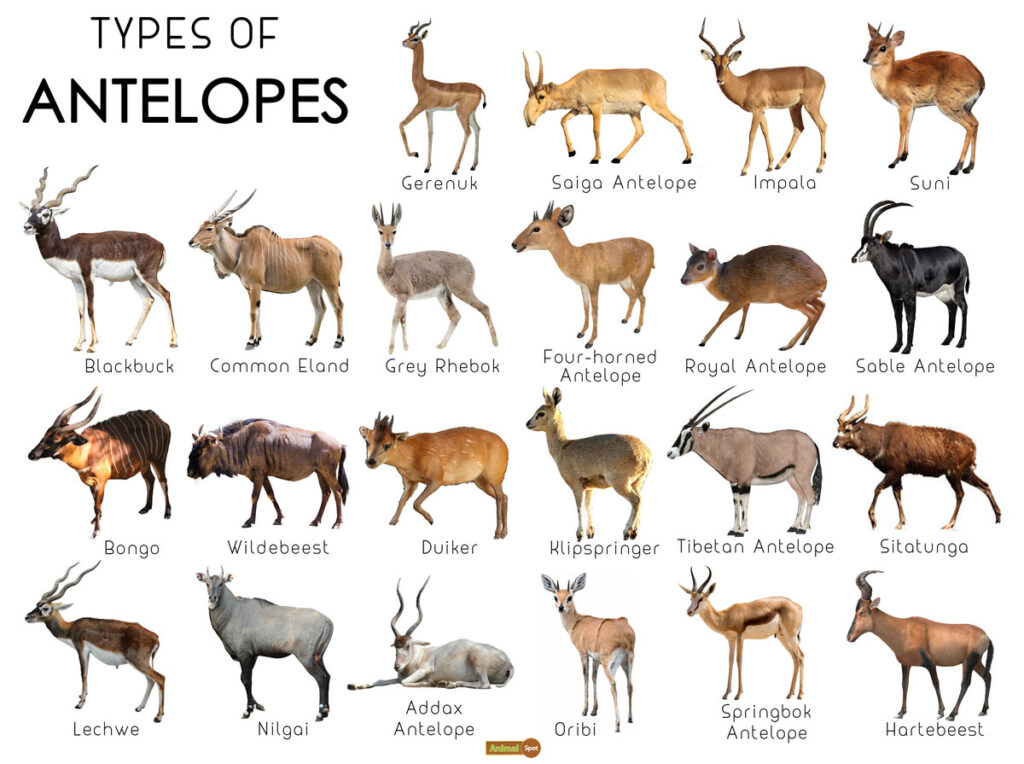

Antelopes are among the most graceful and agile animals found in the wild. These elegant creatures belong to the bovid family, which also includes cattle, goats, and sheep. With over 90 species spread primarily across Africa and parts of Asia, antelopes come in a wide range of sizes and shapes, yet they all share common features like slender builds, alert eyes, and strong legs that make them expert runners and survivors in the wild.

Antelopes are incredibly adaptable, occupying a variety of habitats. While many thrive on open African grasslands and savannas, others are well-suited to different environments such as forests, deserts, mountains, and swamps. For example, gazelles are fast runners built for open plains, whereas species like the duiker and bushbuck prefer dense forests. Desert dwellers like the oryx have adaptations for extreme heat and water scarcity, while swamp antelopes like the sitatunga have long, splayed hooves for moving through wetlands.

Built for speed and agility, many antelopes rely on their swift movements to escape predators. Species like the Thomson’s gazelle can run at speeds exceeding 50 miles per hour (80 km/h), often using zigzagging motions and long leaps to avoid capture. Their physical design—long legs, light frames, and powerful muscles—makes them some of the best runners in the animal kingdom.

One of the most distinguishing features of antelopes is their horns. Unlike deer, antelopes do not shed their horns. In many species, both males and females grow them, although in others, only the males have horns. These are used not only for defense but also in fights for dominance during mating season and in displays of strength to deter rivals. Some species, such as the greater kudu, have spectacular spiral horns that can grow over a meter long.

Antelopes are herbivores, with a diet that varies depending on their habitat. Some are grazers that feed mainly on grasses, while others are browsers that eat leaves, shoots, fruits, and even bark. Their digestive systems are specially adapted to extract nutrients from fibrous plant material, allowing them to survive in areas with sparse vegetation, especially during dry seasons.

Social behavior among antelopes ranges widely. Some species, like the impala, form large herds that provide safety in numbers, helping individuals detect and evade predators. Others, like the steenbok, live alone or in monogamous pairs. Living in groups often comes with shared responsibilities like keeping watch and finding food and water more efficiently.

Despite their impressive adaptations, many antelope species face serious threats. Habitat loss due to human expansion, fencing, and agriculture has reduced their roaming space. Poaching for meat and horns has also pushed some species, like the addax and hirola, to the brink of extinction. Thankfully, conservation efforts—such as protected reserves, breeding programs, and anti-poaching laws—are helping some populations recover.

Some of the most fascinating antelope species include the impala, known for its high jumps and speed; the springbok, famous for its “pronking” leaps; the desert-adapted oryx; the swamp-living sitatunga; and the saiga, easily recognized by its unusual downward-facing nose designed to filter dust.

In conclusion, antelopes are far more than just prey animals on the savanna—they are essential to their ecosystems and stunning examples of nature’s adaptability. Their beauty, speed, and unique traits make them one of the most captivating groups in the animal world. As symbols of the wild and the delicate balance of life, protecting them is vital to preserving biodiversity.