Avenging Greatness: How Alexander’s Father Complex Changed History

Alexander the Great, one of history’s most legendary conquerors, didn’t just carve out an empire through strategy and charisma—his path was deeply shaped by an intense, complicated relationship with his father, King Philip II of Macedon. These “daddy issues,” rooted in admiration, rivalry, and insecurity, weren’t just personal—they had global consequences.

The Shadow of Philip II

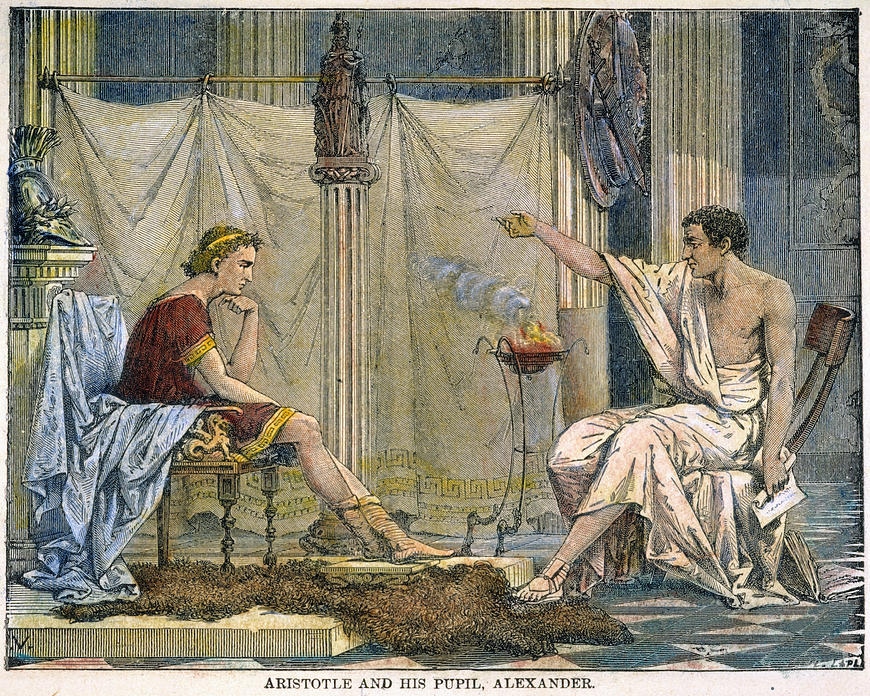

Philip II was a brilliant and ruthless ruler who transformed Macedon from a fractured kingdom into a powerful, unified military state. A skilled general and statesman, he laid the groundwork for Macedonian dominance in Greece. Young Alexander grew up watching his father win battles and outmaneuver enemies both foreign and domestic. Though Alexander was trained by Aristotle and showed immense promise, he lived in Philip’s enormous shadow.

Philip’s military reforms, political cunning, and expansionist ambitions set a high bar. To many in the kingdom, Alexander was just the heir to Philip’s achievements. This stung Alexander, who longed not just to match his father—but to surpass him. When he reportedly said, “My father will leave me nothing great to do,” it wasn’t just teenage angst—it was a prophecy.

The Assassination and Aftermath

In 336 BCE, Philip was assassinated under mysterious circumstances. Rumors swirled that Alexander and his mother Olympias may have been involved. Whether or not Alexander had a hand in the murder, the psychological impact was undeniable: his father was gone, and the throne was now his—but so was the burden of surpassing a legend.

Almost immediately, Alexander began purging rivals, consolidating power, and preparing for war. His decision to invade Persia was not just strategic—it was symbolic. Philip had dreamed of such a conquest. Alexander would not only fulfill it; he would do it better, faster, and more completely.

Conquest as Catharsis

As Alexander swept across Asia Minor, Egypt, and into India, his victories were both military triumphs and emotional vindications. At each step, he seemed to shout to the world—and to the memory of Philip—that he was greater.

He didn’t just defeat enemies; he erased and redefined their worlds. Cities were renamed after him, including over 20 “Alexandrias.” In Egypt, he was declared the son of the god Ammon, rebranding himself as a semi-divine being—a literal replacement for his mortal father.

His destruction of Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of Persia, was more than revenge for past wars. It was theater. It was legacy-building. It was an act of rewriting history—placing his name where others once reigned.

The Father Figure Vacuum

After Philip, Alexander never allowed another true father figure into his life. He trusted and loved his companion Hephaestion but executed trusted generals like Parmenion and Cleitus when they questioned him or reminded him of his mortality.

Eventually, Alexander’s sense of invincibility and isolation grew. His increasing megalomania and demand for godlike reverence alienated many of his men. Yet even in his excess, one can see the flicker of a child still trying to prove something to a ghost.

A World Transformed

By the time of his death in 323 BCE, Alexander had built an empire stretching from Greece to India. More importantly, he spread Hellenistic culture across three continents—fusing Greek ideas with Persian, Egyptian, and Indian traditions. His successors (the Diadochi) fractured his empire but continued the cultural blend that shaped philosophy, art, science, and governance for centuries.

All of this—this tidal wave of cultural change and political transformation—was sparked in part by the unresolved tension between a father and son. Alexander didn’t just inherit a kingdom; he inherited a complex. And in avenging the greatness of his father, he gave the world a new shape.