The Best Evidence Yet That Roman Gladiators Fought Lions: A Bite Mark Through Time

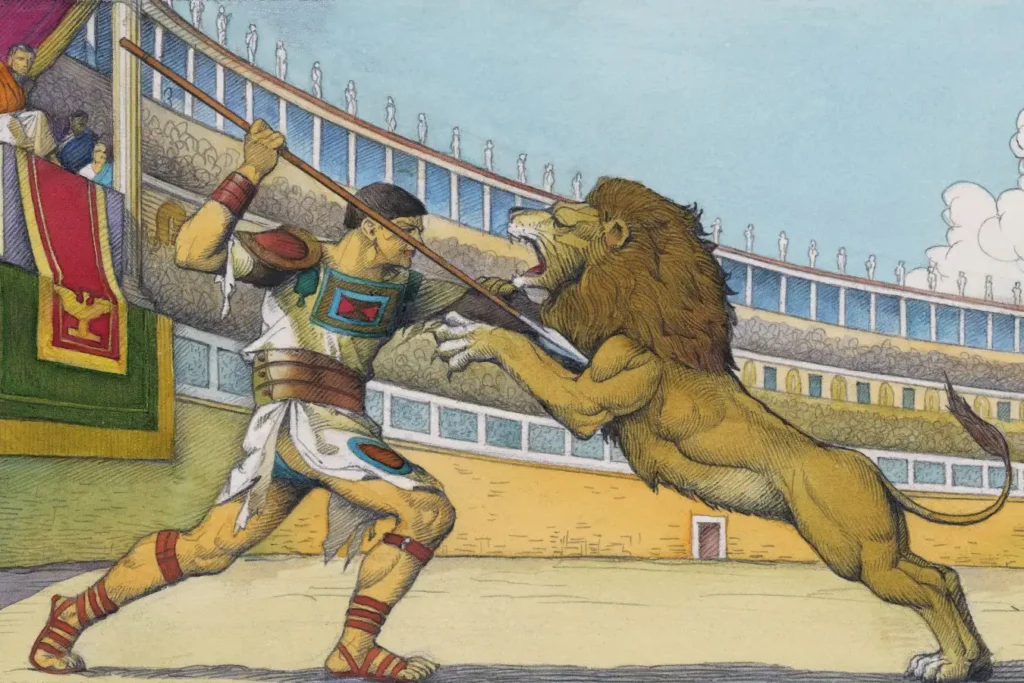

The image of a Roman gladiator locked in deadly combat with a lion is iconic—etched into the popular imagination through films, books, and ancient lore. For centuries, historians debated whether these spectacles were largely theatrical or truly lethal. Now, a single bite mark on a human skeleton may offer the clearest archaeological evidence yet that these epic battles were brutally real.

This remarkable find, unearthed in the ruins of a Roman amphitheater, adds new depth to our understanding of gladiatorial games, animal combat (venationes), and Roman entertainment culture. It transforms speculation into hard science—combining forensic analysis, archaeology, and classical history into one of the most fascinating discoveries of recent years.

🏛️ The Context: Gladiators and the Arena

Gladiator games were a core feature of Roman public life for over 600 years, peaking between the 1st century BCE and 3rd century CE.

There were multiple types of contests in Roman amphitheaters:

- Gladiator vs. Gladiator: Duels between trained fighters.

- Executions (noxii): Condemned criminals faced public death, often by wild animals.

- Venationes: Staged animal hunts, sometimes involving professional hunters or even gladiators.

- Beast-on-human combat: Involving lions, leopards, bears, boars, and exotic imported animals.

These shows served political, social, and religious purposes: glorifying the empire, reinforcing public order, and displaying man’s dominance over nature.

🧬 The Discovery: A Bite That Changed History

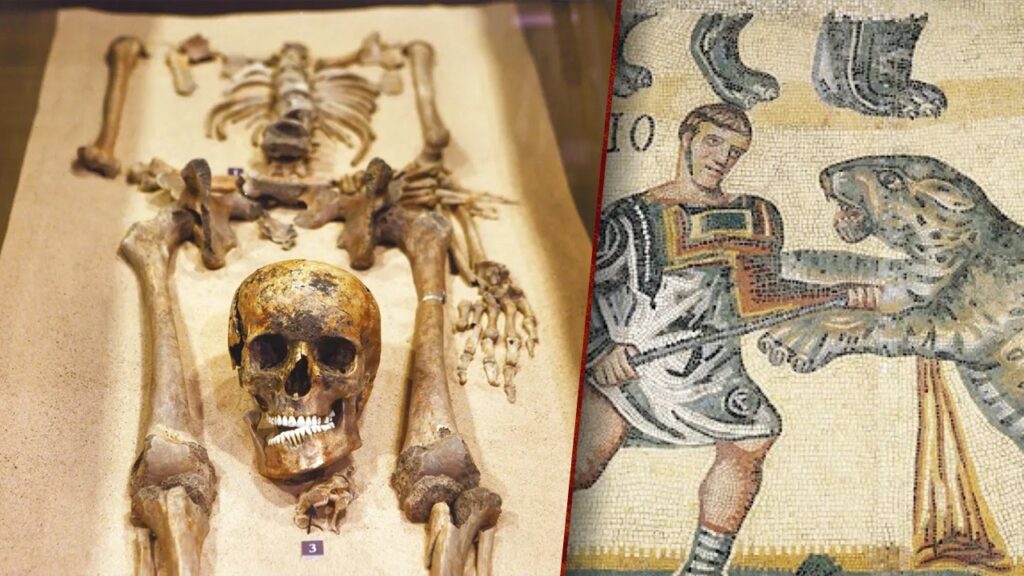

In a Roman amphitheater in Mérida, Spain (ancient Emerita Augusta), archaeologists uncovered a 2,000-year-old human skeleton with a distinct and chilling injury:

- A partially healed bite mark on the pelvis—consistent in size, spacing, and puncture shape with the jaw of a large lion or tiger.

- No signs of surgical intervention or defensive trauma from weapons.

- Clear evidence of survival after the initial injury, indicated by bone remodeling.

This suggests the individual was attacked by a large predator, lived long enough to begin healing, and likely died from follow-up injuries or infection.

The bite offers unprecedented physical evidence of direct combat between a human and a big cat—something no ancient text can provide with such certainty.

📍 Location Significance: Emerita Augusta

Emerita Augusta, founded in 25 BCE, was a major Roman outpost in Hispania (modern Spain) and had a well-preserved amphitheater built specifically for gladiator games and animal combats.

- The skeleton was found in a context directly linked to the arena’s lower levels, where gladiators and animals were held before events.

- This supports the theory that the injured individual was either a gladiator, venator (beast hunter), or condemned criminal used in a public spectacle.

🔍 Forensic and Zoological Analysis

The forensic analysis involved:

- Dental pattern matching: Comparing bite radius and depth with the skulls of lions and tigers.

- CT scanning and 3D modeling: To recreate the bite angle and pressure.

- Bone regeneration patterns: Confirming post-injury survival over weeks or months.

Findings showed the canines pierced deep into the iliac crest (upper pelvic bone), a lethal area if infection set in or if major blood vessels were damaged.

It ruled out dogs, wolves, bears, or other native species, firmly placing the cause as a large exotic predator, most likely imported from North Africa.

🧠 What the Bite Mark Tells Us

This single injury speaks volumes about ancient Rome’s brutal entertainment culture:

- Real Combat, Not Just Theater

While some assumed the lion fights were symbolic or staged, this evidence confirms real-life life-or-death struggles between man and beast. - Trained or Condemned?

The individual may have been a venator, a specialist trained to fight animals, or a noxii, condemned to die for public spectacle. - Social Hierarchy in Bones

Unlike trained gladiators—who were often revered and buried with honors—animal-fighters and criminals rarely received proper graves. The lack of grave goods supports the idea this was a lower-class or enslaved individual.

🦁 The Role of Exotic Animals in Rome

By the 1st century CE, the Roman Empire was importing thousands of exotic animals:

- Lions from North Africa

- Tigers from India

- Bears from Europe

- Elephants from Africa and Asia

- Crocodiles and hippos from the Nile

Many were used in venationes, often massacred en masse for public thrill. One emperor, Titus, killed 5,000 animals in a single day to inaugurate the Colosseum.

The logistics of these imports were staggering—and costly—but they showcased Rome’s imperial reach and dominance.

🏺 Historical Sources vs. Archaeological Evidence

Ancient writers like Seneca, Suetonius, and Martial wrote of men being mauled by beasts, but their accounts are often rhetorical or exaggerated.

Until now, physical proof was elusive. The bite-mark discovery is significant because:

- It corroborates written history with tangible evidence.

- It gives insight into trauma, healing, and death in the arena.

- It reveals the brutal reality beneath the pageantry.

⚖️ Ethical Reflections

This discovery prompts modern questions about the nature of violence as entertainment. The use of animals and human beings as tools for spectacle, however ancient, mirrors some ethical challenges today in animal cruelty, forced labor, and public voyeurism.

Understanding Rome’s legacy through this lens helps frame debates about modern entertainment, justice, and the value of human (and animal) life.

🧠 Conclusion: A Mark That Tells a Thousand Stories

The bite mark on the pelvis of a Roman man offers the most definitive evidence yet that gladiators or criminals really did fight lions—and sometimes lived, even briefly, to tell the tale.

More than just an injury, it’s a historical fingerprint—a physical imprint of the brutal culture of ancient Rome, where blood fueled spectacle and life was both a performance and a punishment.

Through one man’s wound, we glimpse an empire’s identity, ambitions, and appetite for dominance.