“For Ancient Egyptians, Dance Was Life: Rituals, Festivals, and Sacred Motion”

To the ancient Egyptians, dance was not merely an art form or entertainment—it was a sacred, social, and symbolic practice embedded in nearly every aspect of life. From religious rituals and funerary rites to royal celebrations and agricultural festivals, dance held spiritual, social, and cultural significance. Through rhythmic movement, music, and symbolic gestures, the Egyptians communicated with their gods, honored the dead, celebrated life, and bonded as a community.

This article explores the many roles of dance in ancient Egyptian civilization—its performers, purposes, styles, and lasting legacy.

Dance in Egyptian Society: More Than Just Movement

In ancient Egypt (c. 3100 BCE to 30 BCE), dance was deeply interwoven with religion, ceremony, and daily life. Visual depictions from tombs, temples, and papyri—combined with textual records and archaeological evidence—reveal that dance was not a marginal activity, but a revered and vital part of the human experience.

Key Contexts in Which Dance Appeared:

- Religious rituals and temple ceremonies

- Funerary and mourning traditions

- Royal court entertainment

- Festivals and public celebrations

- Agricultural and seasonal rites

- Private banquets and social gatherings

The Spiritual and Religious Significance

Dance played a major role in temple rituals and religious festivals. It was often used as a way to worship deities, honor the divine order (Ma’at), and facilitate communication between humans and gods.

Deities and Dance:

- Hathor, the goddess of love, music, fertility, and dance, was particularly associated with joyous, sensual dance.

- Bastet, the feline goddess of home and fertility, was honored with energetic music and festive dances.

- Osiris, the god of the afterlife, was venerated through ritual dances symbolizing death and resurrection.

Priests and priestesses, as well as trained temple dancers, performed sacred choreographies believed to mirror cosmic movements and maintain balance in the world. These rituals often included sistrum music, drums, flutes, and elaborate costumes.

Dance and Death: Funerary Traditions

Dance was also integral to mourning rituals and funerals. Muu dancers—usually male performers dressed in papyrus skirts or costumes resembling ancestral spirits—danced during funeral processions to guide the soul of the deceased to the afterlife. These dances were both solemn and protective, designed to ward off evil spirits and ensure safe passage.

Women also participated in funerary dances, often expressing intense grief through stylized, repetitive movements, wailing, and dramatic gestures—believed to help ease the transition from life to death.

Professional Dancers and Their Status

Professional dancers in ancient Egypt were often trained from a young age and could achieve considerable status and prestige, especially those who performed in royal courts or temples.

There were different types of dancers:

- Solo dancers: Highly skilled, performing interpretive or acrobatic routines.

- Group dancers: Synchronized performers who danced in pairs or circles.

- Temple dancers: Considered spiritually pure, often part of religious orders.

- Banquet dancers: Entertainers hired to perform at feasts, parties, and weddings.

While many dancers were women, male dancers also played prominent roles, especially in martial, funerary, and acrobatic performances.

Dancers often belonged to guilds or troupes, and their images appear in tomb paintings, sometimes alongside musicians and acrobats. Tomb inscriptions sometimes list them by name, indicating a respected profession.

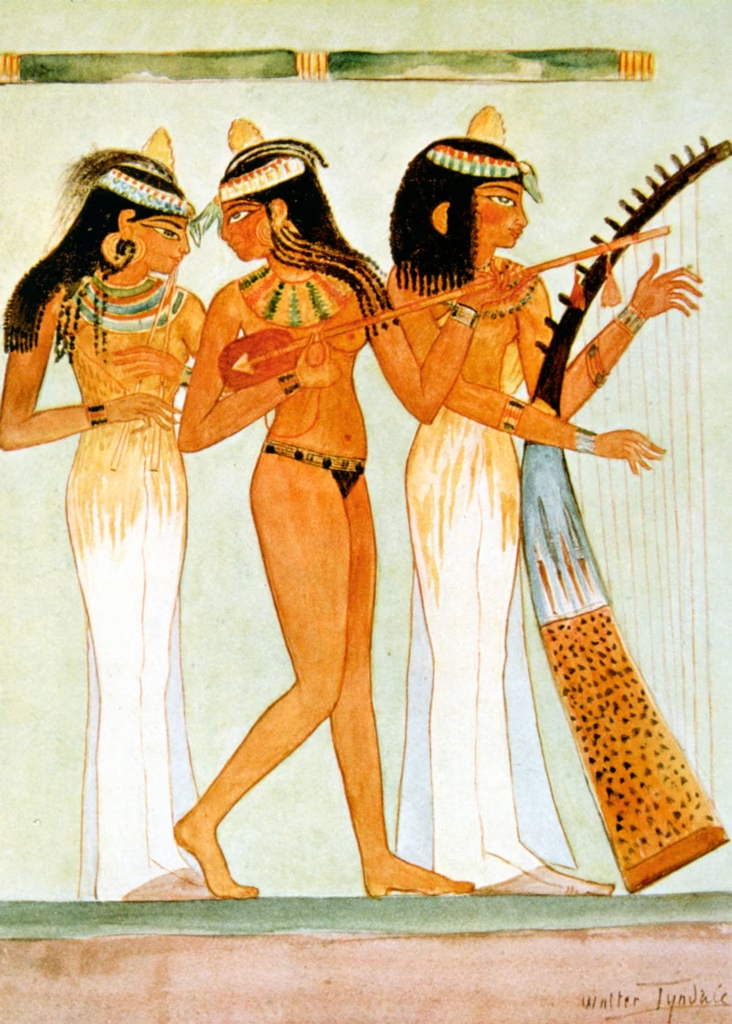

Costumes, Instruments, and Styles

Ancient Egyptian dance was accompanied by music and characterized by symbolic gestures, rhythmic movements, and expressive postures rather than the freeform styles of modern dance.

Common Features of Egyptian Dance:

- Graceful arm and hand movements

- Bending and turning the body

- Emphasis on isolated body parts (shoulders, hips, head)

- Slow, deliberate rhythms for religious dances; faster for festivals

Costumes and Adornments:

- Flowing linen garments, often sheer or intricately pleated

- Jewelry, including wide collars, bracelets, and anklets

- Scented cones on the head, releasing perfume during performances

- Makeup with kohl-lined eyes and painted faces to emphasize expressions

Musical Accompaniment:

- Sistrum: Sacred rattle often associated with Hathor

- Drums and tambourines

- Flutes and reed instruments

- Clapping, finger snapping, and hand percussion

The music helped dictate rhythm, emotion, and structure for the dancers.

Dance in Festivals and Daily Life

Public and religious festivals often involved dancing in the streets. Events like the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, the Opet Festival, or the Festival of Hathor featured dancing processions, ritual performances, and community-wide celebrations.

In daily life, dance could be seen at:

- Weddings and family gatherings

- Agricultural festivals celebrating planting or harvest

- Military victories or royal commemorations

Dance was also enjoyed privately, as suggested by depictions of home banquets and intimate gatherings where dancers entertained guests with music and movement.

Depictions in Art and Archaeology

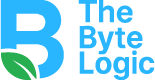

Our understanding of Egyptian dance comes primarily from visual sources, as detailed choreographic notation did not survive. Tomb paintings, relief carvings, and papyrus illustrations provide vibrant scenes of dancers in motion.

Key Sites with Dance Representations:

- Tomb of Nebamun (c. 1350 BCE): Depicts banquet scenes with graceful female dancers.

- Theban tombs: Feature images of Muu dancers and funerary processions.

- Temple reliefs of Hathor and Bastet: Show ritual dancers in sacred contexts.

These visual sources provide a unique glimpse into the energy, elegance, and emotional depth of Egyptian dance.

Enduring Legacy

Though thousands of years have passed, the essence of ancient Egyptian dance lives on:

- In Middle Eastern and North African folk dances influenced by ancient traditions.

- In modern interpretations of “Egyptian-style” dance seen in belly dance, classical ballet, and performance art.

- In scholarly studies that decode movements from ancient visual records.

The spiritual and symbolic dimensions of Egyptian dance still inspire artists, choreographers, and historians today.

Conclusion: Movement as Life, Ritual, and Expression

For the ancient Egyptians, dance was a sacred language—a means to express joy, grief, prayer, celebration, and cosmic harmony. Whether honoring gods, comforting the dead, or entertaining guests, movement served as both a physical and metaphysical connector between people, nature, and the divine.

Far from a marginal art, dance was a central thread in the cultural fabric of ancient Egypt, reflecting the rhythms of life and the enduring pursuit of balance, beauty, and order in a world guided by Ma’at.