“City of Fur and Feather: Animals in the Streets of Medieval London”

Medieval London wasn’t just a bustling city of merchants, guilds, monks, and royalty—it was also a city teeming with animals, both wild and domesticated. From the working beasts that kept the city alive to the pets that shared homes with nobles and commoners, animals were central to every aspect of life in medieval London.

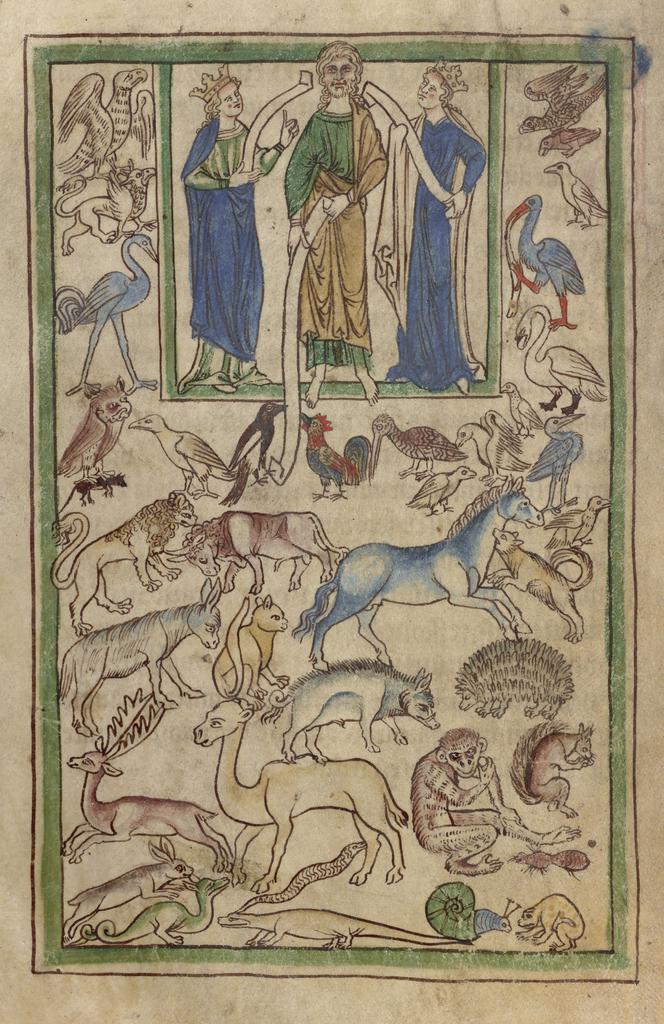

They walked the same narrow streets, filled the same markets, were depicted in manuscripts, and were the subject of both law and lore. Exploring the role of animals in medieval London reveals not just how people lived, but how they understood nature, society, and the divine order of the world.

1. Horses, Oxen, and Donkeys: The City’s Powerhouses

In a time before engines, animals were essential laborers. Horses were used for transportation, courier work, and war. While noblemen rode warhorses (destriers), London’s merchants and messengers relied on more manageable riding horses and palfreys.

- Cart-horses and oxen hauled heavy goods, including barrels of wine, timber, or wool, through the muddy streets.

- Donkeys were the preferred beasts of burden for poorer citizens and peddlers.

- Stables were found in every ward, and horse dung was a common part of the city’s pungent atmosphere.

Horses were so important that laws regulated their treatment, and harming a valuable beast could result in harsh punishment.

2. Pigs and Goats: Living Garbage Collectors

Perhaps the most iconic—and problematic—urban animal of medieval London was the free-roaming pig.

- Scavenger pigs wandered city streets, eating scraps and refuse, effectively serving as mobile garbage disposals.

- They were considered a health hazard and frequently caused accidents; royal decrees periodically banned them, but the bans were hard to enforce.

Goats also roamed parts of the city, kept for milk and meat. Both animals were symbols of poverty but essential to urban survival.

3. Dogs: From Guardians to Gentle Companions

Dogs in medieval London served practical and social roles:

- Watchdogs were used to guard homes and workshops.

- Hunting hounds were prized possessions of the nobility and often detailed in legal records and wills.

- Lapdogs, especially greyhounds and toy spaniels, were kept by elite women, sometimes even wearing decorative collars and bells.

London’s city records include complaints about strays, dog fights, and bites. Some dogs even accompanied beggars, prompting both compassion and complaint from officials.

4. Cats: Pest Control and Occult Symbol

Cats were valued for their ability to catch mice and rats, especially in shops, homes, and granaries. But their cultural reputation was complex:

- Cats were associated with witchcraft and bad luck, particularly black cats.

- They were also seen as mystical creatures tied to feminine energy and the night.

- In religious art, they occasionally symbolized heresy or independence—a trait viewed with suspicion.

Despite this, many Londoners kept cats, and some manuscripts show affectionate depictions of felines curled up beside monks.

5. Poultry and Birds: Livestock and Liturgy

Chickens, geese, and ducks were common in backyards and markets.

- Eggs and meat were essential dietary staples.

- Geese provided both food and feathers for writing quills.

- Urban bird-keeping was so widespread that laws were introduced to manage noise and hygiene.

More elite birds, like falcons and hawks, were kept for hunting. Falconry was a noble pursuit, and possession of certain birds was restricted by class.

Pigeons were kept in dovecotes for food, and church spires were filled with their nests.

6. Exotic Animals: Medieval Marvels

From the 12th century onward, royal menageries began to appear. The Tower of London hosted an exotic collection:

- Lions, leopards, and an elephant were housed there, gifts from foreign rulers.

- These animals were not just curiosities, but symbols of royal power and divine favor.

- Care for these beasts was poor by modern standards, but they were a marvel to common Londoners.

Medieval manuscripts and bestiaries sometimes exaggerated these animals’ features, blending observation with myth.

7. Rats, Mice, and the Unseen

The medieval city teemed with rodents. Rats and fleas were omnipresent, playing a role in the outbreaks of plague, including the Black Death (1348–1350).

Although medieval people did not understand germ theory, they associated filth with illness and knew rats brought death.

Rats were the enemies of bakers, brewers, and grain dealers. Cats, dogs, and traps were used for control, though largely ineffectively.

8. Animals in Markets and Butchers’ Rows

Animals were at the heart of London’s economy:

- Smithfield Market was the primary site for the buying and selling of livestock—cattle, sheep, and pigs.

- Poultry sellers and fishmongers dominated other parts of the city.

- Butchering often took place in the open air, and animal remains polluted the Thames, contributing to the city’s terrible stench.

Tanners and leatherworkers relied on hides, and bones were turned into tools, dice, or ornaments.

9. Symbolism, Religion, and the Law

Animals were not just part of daily life—they were embedded in religion, law, and myth.

- The church used animal imagery to teach morality—lambs for innocence, lions for Christ, serpents for sin.

- Bestiaries, richly illustrated medieval books, cataloged real and mythical animals as part of God’s creation.

- Animals were sometimes tried in medieval animal trials—yes, pigs were actually prosecuted for harm or destruction.

- Saints often had animal companions—St. Cuthbert and the otters, St. Francis and the birds.

Conclusion: Creatures of Fur, Feather, and Faith

The animals of medieval London were not just background figures—they were essential citizens of the city. They ploughed its fields, cleaned its scraps, carried its burdens, comforted its people, and even inspired its art and theology. From grimy alleyways to cathedral altars, animals shaped the rhythm and meaning of life.

Their lives—often brutal, short, or sacred—reflect the complex relationship medieval people had with nature. Part practical, part spiritual, always interwoven.

In understanding them, we understand London’s past not just as a human story, but as a living ecosystem—one built by hands, hooves, paws, and wings.