Smuggling Under the Cover of Plague: How Crisis Fueled the Black Market

Plagues are often remembered for the terror they unleash—bodies in the streets, cities in lockdown, and widespread death. But beneath the surface of public panic and collapsing economies, another story has repeatedly played out: the rise of smuggling and black-market activity.

From medieval Europe’s Black Death to early modern quarantine laws, smugglers exploited disease-ridden chaos to move contraband, evade taxes, and subvert authority. In the shadows of pandemic restrictions, a parallel economy flourished, often with the quiet cooperation—or desperate consent—of the people and even officials.

This article explores how plague and pandemic conditions unintentionally fueled smuggling, turning illness into opportunity for the daring, the desperate, and the criminal.

1. The Black Death and the Breakdown of Trade (1347–1351)

When the Black Death struck Europe in the mid-14th century, it killed an estimated one-third of the continent’s population. With towns depopulated, ports closed, and supply chains shattered, a demand for goods remained—but legitimate means of acquiring them often didn’t.

What Was Smuggled:

- Spices, silks, and exotic goods once traded openly through Mediterranean ports were smuggled overland or by smaller, illicit vessels.

- Basic necessities like grain, wine, and salt were hoarded and traded secretly to avoid price controls or quarantines.

- Religious relics and valuables, especially from looted churches or abandoned homes.

Why Smuggling Flourished:

- Local authorities were overwhelmed or dead.

- Cities closed gates or imposed harsh taxes on goods.

- People feared contamination through official trade channels, making black-market sources more attractive.

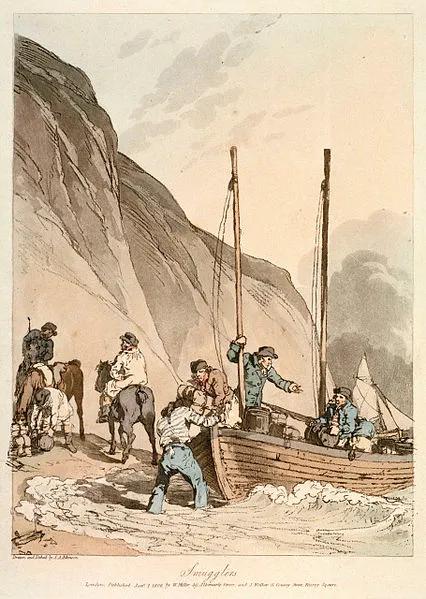

2. Quarantine and the Rise of Coastal Smugglers (15th–17th Centuries)

As understanding of contagion improved—though still based on flawed theories—European port cities began enforcing quarantine laws to isolate incoming ships and goods for weeks at a time.

Venice & the Lazaretto Model:

Venice pioneered quarantine stations (lazaretti) on nearby islands where ships and crew were held. While effective against disease, it created a bottleneck for commerce.

Smuggler Tactics:

- Night landings on unguarded coves to avoid quarantine.

- False manifests and forged papers to pass inspections.

- Bribery of plague officials, who were often poorly paid or dying themselves.

Notable Example:

During the plague outbreaks in Marseille (1720), smugglers were blamed for reintroducing contaminated cloth and goods—despite official port restrictions. Black market imports continued because local elites needed goods and had the means to bypass restrictions.

3. Plague Laws as Weapons and Loopholes

Plague restrictions often created not just health safeguards but economic tools. Rulers and merchants used plague laws to protect monopolies, punish rivals, or secure trade advantages. Smugglers responded by exploiting these same laws.

Examples:

- Blocking rival trade under the pretext of “infection risk” while permitting favored merchants.

- Relabeling or disguising goods to get around restrictions.

- Smuggling across land borders where enforcement was weaker than at ports.

In many cities, smuggling syndicates included local officials, who accepted bribes or shares of the profit.

4. Smuggling During the London Plague (1665–66)

The Great Plague of London caused mass panic and harsh restrictions: infected homes were sealed, trade was frozen, and city gates monitored. But with thousands dying and the government paralyzed, informal economies boomed.

Smuggled Goods:

- Food and medicine were brought in by night—often through dangerous slum alleyways.

- Alcohol was smuggled past curfews and into quarantined areas.

- Bodies and valuables were illegally removed from homes to avoid property confiscation or cremation.

Notably:

Some smugglers posed as plague doctors or watchmen, gaining access to locked neighborhoods. Others bribed their way past guards at the city wall.

5. The Ethics of Smuggling During Plague

Not all plague-era smuggling was purely criminal. Many viewed it as a moral response to immoral conditions:

- When officials abandoned towns, smugglers kept food supplies flowing.

- In poor communities, trading outside the law was the only way to survive.

- In some cases, smuggling helped bypass corruption, as state-sanctioned merchants gouged prices.

However, smuggling also contributed to the spread of disease when infected goods were moved illicitly. Cloth, grain, and even pets sometimes carried plague into uninfected regions.

6. Legacy and Parallels in Later Pandemics

Even beyond the medieval period, pandemics continued to fuel underground trade:

- During the Spanish Flu (1918–1919), alcohol was smuggled under the guise of medicine, especially in prohibition-era North America.

- Modern epidemics (Ebola, COVID-19) saw the rise of black markets for masks, medicine, and smuggling across closed borders.

Every time official systems are overwhelmed by disease, informal networks rise to fill the gaps—for better or worse.

Conclusion: Illness, Desperation, and the Shadows of Trade

Plague didn’t just reshape cities through death—it reshaped economies through necessity. Smuggling under the cover of plague reveals the resilience and opportunism of underground economies and exposes the vulnerabilities in official structures.

It shows how crises—especially health crises—create spaces where law, morality, and survival intersect in complex, often contradictory ways. Smugglers were villains to some, saviors to others, and survivors above all.

And while the diseases may have changed, the pattern remains: when the gates close, the shadows open.