“Born of the Land: Why the U.S. Has Birthright Citizenship”

🗽 Introduction: The Question of Who Belongs

In an era of increasing debate over borders, immigration, and national identity, one legal concept stands at the heart of American citizenship: birthright citizenship. Enshrined in the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, it ensures that anyone born on U.S. soil—regardless of their parents’ citizenship or immigration status—is automatically a citizen of the United States.

But where did this idea come from? Why was it codified into law? And why has it become a flashpoint in modern political discourse?

This article traces the historical origins, legal battles, and current challenges surrounding birthright citizenship—revealing why this principle is not just a legal technicality, but a foundational element of American democracy.

⚖️ The Legal Principle: Jus Soli vs. Jus Sanguinis

Birthright citizenship is based on the Latin principle of jus soli (“right of the soil”). Under this doctrine, a person becomes a citizen simply by being born within a country’s territory. This contrasts with jus sanguinis (“right of blood”), in which citizenship is determined by the nationality or ethnicity of one’s parents.

Most countries today use jus sanguinis. But the United States is one of a handful of nations—including Canada and several Latin American countries—that uphold unconditional jus soli.

📜 The Origins: English Common Law and Colonial Roots

The United States inherited much of its legal tradition from English common law, which embraced jus soli dating back to the early 17th century. The landmark case of Calvin’s Case (1608) established that anyone born under the King’s protection was a natural-born subject, regardless of parental origin.

American colonial governments followed suit. Even before independence, the colonies generally recognized that birth on American soil conferred subjecthood, and later, citizenship.

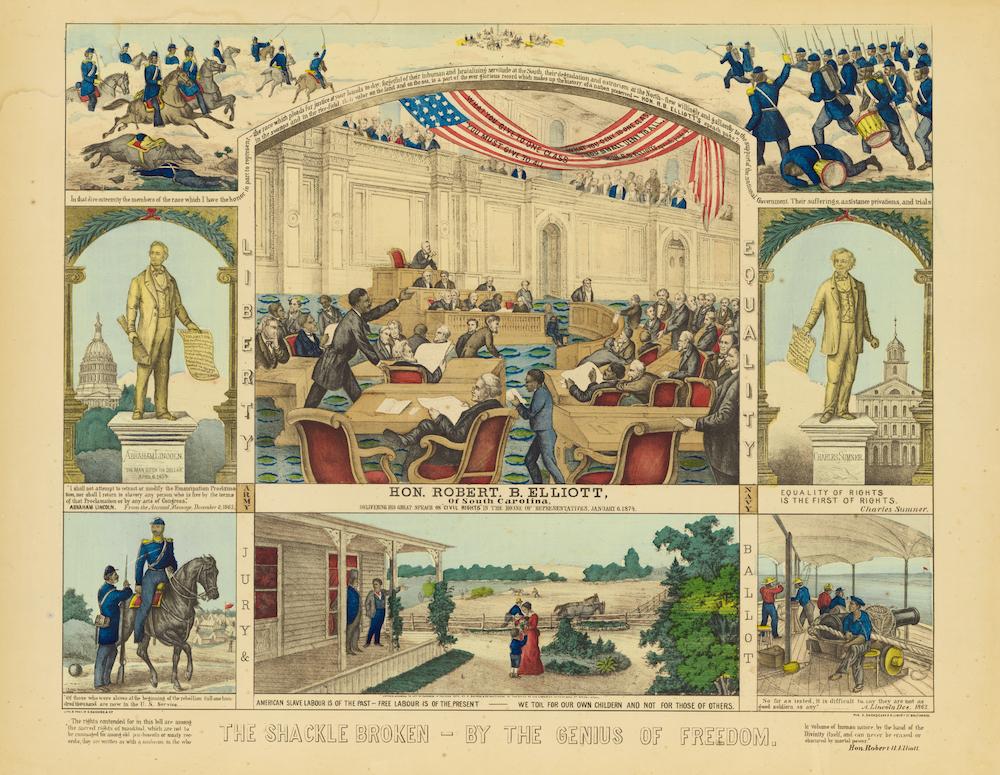

🩸 The Complication: Race, Slavery, and Dred Scott

The broad embrace of birthright citizenship met a significant challenge in the 19th century with the rise of racialized legal doctrines. The 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision by the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Black Americans, enslaved or free, could never be citizens of the United States.

This decision shocked abolitionists and anti-slavery advocates, and became one of the catalysts for the Civil War. The case also highlighted the need to clarify the legal boundaries of citizenship.

🛡️ The 14th Amendment: Citizenship Codified

In 1868, following the Civil War, Congress ratified the 14th Amendment to ensure legal equality and end the legacy of slavery. The first sentence of Section 1 declares:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.”

This landmark clause:

- Overturned Dred Scott

- Granted citizenship to formerly enslaved people

- Solidified jus soli as a constitutional right

Importantly, the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” was intended to exclude:

- Children of foreign diplomats

- Children born to enemy occupiers

- Certain Native American tribes (until they were later included by the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924)

⚖️ Wong Kim Ark (1898): The Supreme Court Speaks

The principle of birthright citizenship was affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898).

- Wong Kim Ark, born in San Francisco to Chinese immigrant parents (non-citizens), was denied re-entry into the U.S. after a trip abroad.

- The court ruled 6–2 that he was a U.S. citizen by birth, regardless of his parents’ nationality.

This decision established a binding precedent that even the U.S.-born children of non-citizens (so long as they are subject to U.S. law) are natural-born citizens.

🧠 Legal Interpretation of “Subject to the Jurisdiction”

The phrase “subject to the jurisdiction” has been debated in political and legal circles. Courts have interpreted it to mean anyone:

- Not a foreign diplomat

- Not a member of an enemy military

- Living under and subject to U.S. law

Thus, even undocumented immigrants’ children, if born in the U.S., are citizens—because their parents are subject to U.S. law (they can be arrested, taxed, and tried).

🇺🇸 Contemporary Debate: Politics, Identity, and Law

In recent decades, birthright citizenship has become a hot-button political issue.

Arguments for preserving it:

- It provides equal treatment and legal clarity

- Helps prevent statelessness

- Is firmly rooted in the Constitution

- Ensures integration of immigrant families

Arguments against it (mostly from conservative critics):

- Encourages “anchor babies” or birth tourism

- Undermines immigration control

- Should only apply to children of legal residents or citizens

Political Attempts to End It:

- Multiple bills have been introduced in Congress since the 1990s to restrict birthright citizenship—but none have passed.

- In 2018 and again in 2023–2025, former President Donald Trump proposed ending birthright citizenship via executive order—an action many legal scholars argued was unconstitutional.

- Courts have thus far blocked these attempts, citing the 14th Amendment and Wong Kim Ark.

🌎 Global Comparison

The U.S. stands nearly alone among developed countries in maintaining unrestricted birthright citizenship. Many countries that once offered it—such as France, Ireland, and Australia—have since modified their laws to include parental residency or citizenship requirements.

Yet, the U.S. maintains that citizenship is a birthright, not a privilege—an idea deeply woven into its national identity.

🏛️ Why Birthright Citizenship Still Matters

- It Prevents Discrimination: Citizenship at birth prevents the creation of a legally underprivileged class.

- It Simplifies Legal Status: Clear birthright rules prevent bureaucratic confusion and ensure children’s access to health care, education, and services.

- It Embodies Constitutional Equality: All people born in the U.S. are equal under the law, a principle rooted in the Civil Rights era.

- It Reflects American Values: The U.S. is a nation of immigrants. Birthright citizenship affirms that identity is not inherited but earned through shared soil and laws.

📜 Conclusion: A Legacy Worth Defending

“Born of the land” is not just a poetic phrase—it’s a constitutional promise, forged in the wake of slavery, tested in courts, and renewed in each generation. As modern political winds shift, the principle of birthright citizenship remains a cornerstone of American democracy: a reminder that citizenship begins not in lineage, but in belonging.