“A Nation in Panic: The Mad Cow Crisis of the 1990s”

The Mad Cow Disease crisis—officially known as the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) outbreak—was one of the most shocking public health and agricultural disasters in modern British history. Emerging in the 1980s and peaking during the 1990s, the crisis not only devastated Britain’s cattle industry but also exposed dangerous gaps in food safety, shook public trust in government, and led to a reevaluation of farming practices across the world.

Origins and Emergence of the Disease

BSE was first identified in 1986 in the United Kingdom, when veterinarians noticed a mysterious, degenerative brain condition affecting cattle. Infected cows displayed alarming symptoms: staggering, nervousness, weight loss, and strange behavior—earning it the nickname “mad cow disease.”

The disease is caused by prions, which are misfolded proteins that damage brain tissue, creating a sponge-like appearance in the brain. What made BSE particularly frightening was the fact that prions are virtually indestructible—resistant to heat, chemicals, and standard sterilization processes.

The root cause of the outbreak was eventually traced to contaminated animal feed. In the 1970s and 1980s, it became common practice to feed cattle with processed meat and bone meal (MBM) made from the remains of other animals—including sheep, some of which were infected with scrapie, a similar prion disease. This cannibalistic feeding practice allowed BSE to spread rapidly among the UK’s cattle population.

The Spread and Scale of the Crisis

By the early 1990s, tens of thousands of cattle were infected, and the disease had begun to affect the broader agricultural economy. Despite mounting evidence, British officials were slow to act decisively, reassuring the public that beef was safe to eat.

The situation worsened in 1996, when the UK government made a grim announcement: BSE had likely spread to humans. A new, fatal condition called variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD) had been identified in people who had consumed infected beef. Like BSE in cows, vCJD in humans destroyed brain tissue, caused severe neurological symptoms, and was invariably fatal.

The public reaction was one of outrage, fear, and confusion. Beef sales plummeted. The European Union banned the export of British beef in March 1996—a ban that would remain in place for over a decade. Over the next few years, more than 4 million cattle were slaughtered in Britain in a massive containment effort.

Government Response and Public Outcry

The British government faced heavy criticism for its handling of the crisis. For years, officials had downplayed or denied any human risk, even as cases of BSE soared. When the truth emerged, public trust in the government—particularly the Ministry of Agriculture—collapsed. The issue revealed serious flaws in food safety regulation, transparency, and political accountability.

In response, major reforms were enacted. The UK government introduced a total ban on feeding animal protein to ruminants, strict tracing systems for meat products, and tighter controls on slaughter practices. In 2001, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) was created as an independent watchdog to oversee food safety and restore public confidence.

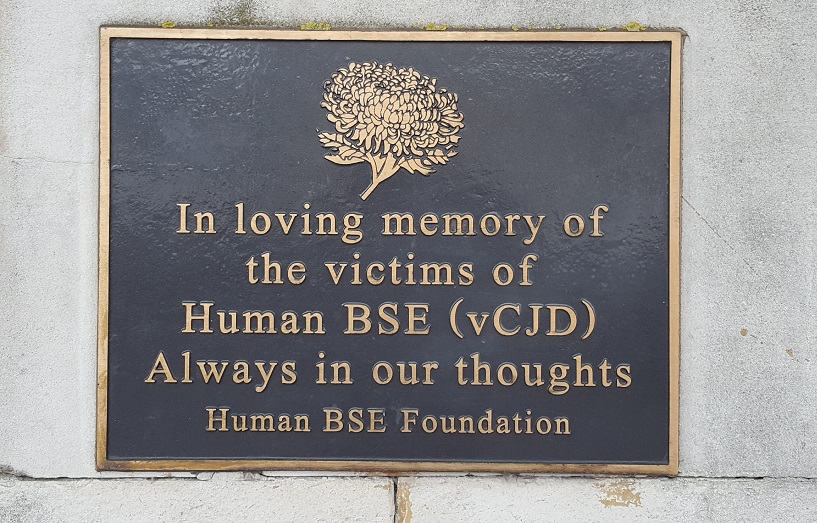

Human Toll and Lingering Effects

By 2022, nearly 180 people in the UK had died of vCJD. While the number was small relative to the population, the disease’s terrifying nature—long incubation, neurological devastation, and lack of treatment—left a lasting scar on the public psyche.

There was also a moral reckoning: the industrial efficiency that had come to dominate modern farming had resulted in tragic consequences. The crisis raised ethical questions about animal welfare, mass production, and public health safeguards.

The psychological and economic effects lingered for years. British farmers faced bankruptcy. The nation’s once-proud cattle industry was brought to its knees. For many, the BSE crisis became a symbol of government failure, industrial greed, and the hidden dangers of modern food systems.

International Impact and Global Reforms

The UK’s BSE crisis sent shockwaves around the world. Dozens of countries imposed bans on British beef, and fears of prion contamination spread internationally. Cases of BSE appeared in other countries—France, Canada, and even the United States—prompting global reviews of animal feed practices and food safety legislation.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Union implemented major changes to prevent prion diseases. Surveillance systems were set up, animal feed practices were overhauled, and extensive testing protocols were introduced to prevent another outbreak.

Legacy and Lessons Learned

The Mad Cow Disease crisis is remembered as a turning point in food safety and agricultural regulation. It exposed the hidden dangers of industrial farming, the need for scientific transparency, and the perils of political inaction. The scandal forced reforms that reshaped how governments, scientists, and the public approach food traceability, biosecurity, and ethical animal husbandry.

Although BSE is now rare, its legacy remains etched in public memory. The crisis taught Britain—and the world—that public health cannot be compromised for economic convenience, and that when dealing with food systems, long-term safety must trump short-term gain.