“Mothers of the Past: A History of Childbirth in the 1800s”

Introduction: A Time of Risk and Resilience

In the 19th century, pregnancy and childbirth were both ordinary and perilous aspects of a woman’s life. Without the medical advancements of the modern era, becoming a mother was deeply intertwined with cultural norms, religious beliefs, domestic expectations, and a constant threat of death. While each woman’s experience varied depending on her social class, location, and race, one truth remained universal: childbirth was a defining and dangerous moment.

This article explores the realities of pregnancy and childbirth in the 1800s, examining the medical knowledge, social customs, maternal care, and risks faced by women in both urban and rural settings.

Understanding Pregnancy in the 19th Century

🍼 Detection and Beliefs

Pregnancy in the 19th century was usually recognized by missed periods, nausea, and physical changes. There were no pregnancy tests—intuition and experience often guided women’s recognition. Pregnancy was considered natural, private, and often not discussed publicly until later in gestation.

In some households, especially among the upper and middle classes, it was even considered improper to mention pregnancy in polite company. Women “with child” might suddenly disappear from public life, retreating from society until the baby was born.

Prenatal Care: Limited and Largely Domestic

There was no formal prenatal care system. Women relied on:

- Family traditions

- Midwives

- Home remedies

- Occasionally, physicians (mainly for wealthier women)

Typical prenatal advice included:

- Avoiding stress and excitement

- Limiting physical activity

- Eating modestly

- Avoiding “emotional shocks”

Some superstitions warned against looking at “ugly” things or having negative thoughts, as these might influence the child’s appearance or temperament.

Nutrition during pregnancy was poorly understood. Ironically, many doctors advised against weight gain, which may have contributed to malnourishment in some cases.

Role of the Midwife and Physician

Throughout most of the century, midwives remained the primary birth attendants, especially in rural areas and among working-class or enslaved women. Midwifery was based on traditional knowledge, passed from generation to generation.

However, with the rise of scientific medicine, male physicians increasingly entered the field of obstetrics, especially in cities and elite households. This led to:

- Greater use of forceps

- Introduction of anesthesia (ether, chloroform)

- A shift in births from homes to hospitals, late in the century

This transition was controversial and often dangerous. Many early hospital births resulted in higher mortality due to poor hygiene and lack of understanding of infection control.

Childbirth: A Woman’s Trial

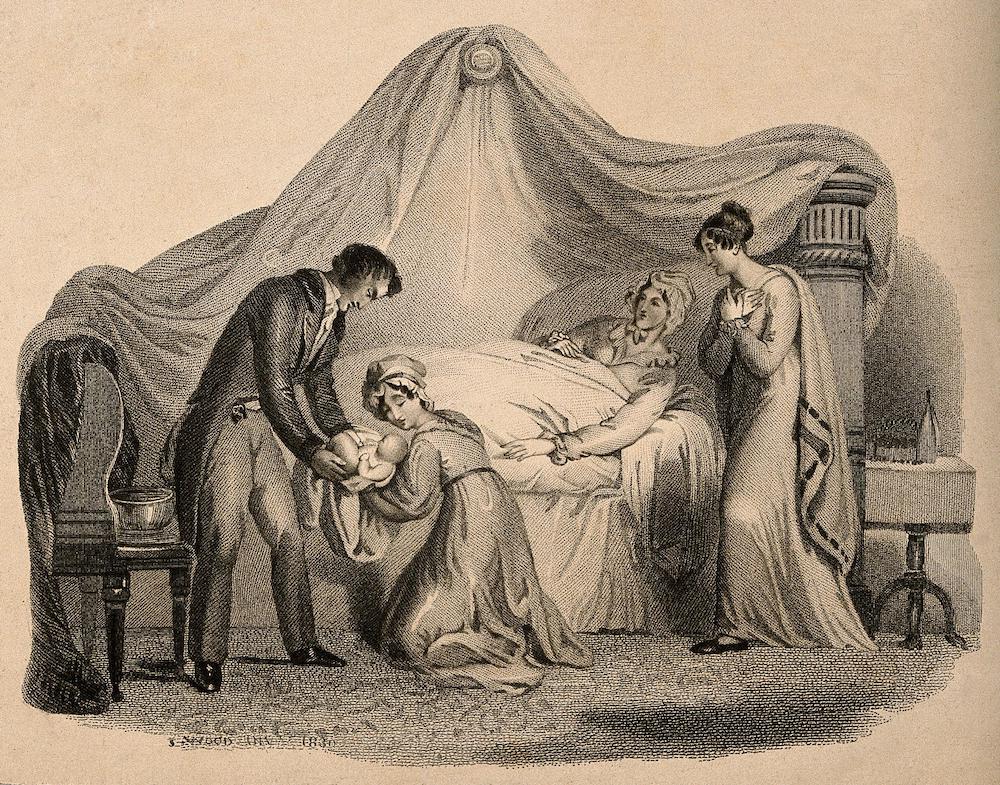

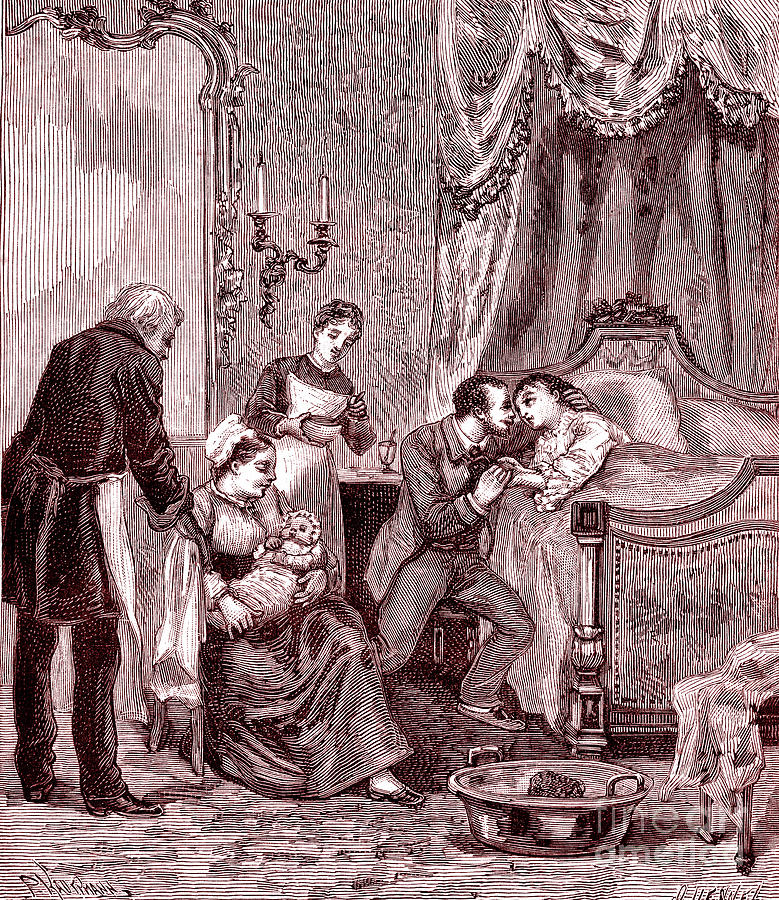

🌒 The Birth Process

Most women gave birth at home, attended by female relatives and a midwife. Labor could last hours—or even days. There were no epidurals or IV fluids. Common practices included:

- Using warm cloths and massage

- Praying or reading scriptures

- Drinking herbal teas to speed labor

For difficult births, forceps were sometimes used—often improperly, causing trauma to mother and baby.

🩸 Dangers and Death

The leading causes of maternal mortality were:

- Puerperal fever (postpartum infection)

- Hemorrhage

- Obstructed labor

- Eclampsia (seizures due to high blood pressure)

Because antiseptics were not widely used until the late 1800s, infections were rampant, especially in hospitals. The discovery of germ theory by Louis Pasteur and its application to obstetrics by Ignaz Semmelweis were revolutionary—but slow to gain acceptance.

Infant mortality was also high. As many as 1 in 4 babies died before their first birthday in some areas.

Postpartum Recovery and Confinement

After childbirth, women underwent “lying-in”—a period of rest, usually 4 to 6 weeks, where the new mother was expected to remain in bed or indoors.

Upper-class women often had wet nurses or servants to assist, while working-class women had to return to labor quickly.

Postpartum depression was poorly understood and often attributed to “female hysteria” or spiritual weakness. Emotional suffering was typically endured in silence.

Social and Cultural Context

💍 Marriage and Motherhood

Motherhood was seen as the primary purpose of womanhood, especially in Victorian society. Women were expected to bear many children; large families were common.

A woman’s fertility was tied to her moral character. Infertility, miscarriage, or stillbirth were often met with shame or silence, especially in wealthier families.

🧑🏽🌾 Class and Race Disparities

- Enslaved and Indigenous women experienced horrific abuse during pregnancy and childbirth, often forced to return to work immediately or subjected to non-consensual experimentation.

- Poor women lacked access to medical care and often died in childbirth unnoticed.

- Wealthy women had better access to physicians but faced risks from over-medicalization and early hospital interventions.

Late 19th-Century Developments

By the 1880s–1900s, new medical tools and theories began transforming childbirth:

- Introduction of germ theory and antiseptics

- Wider (but still limited) use of chloroform and ether

- Medical schools began formal training in obstetrics

- Early maternal health campaigns emerged in urban centers

However, change was slow, and many of these benefits were reserved for wealthier, white women.

Conclusion: The Hidden Labor of Life

Pregnancy and childbirth in the 19th century were deeply rooted in tradition, hardship, and female solidarity. For millions of women, giving birth was both a moment of personal transformation and a test of survival.

Despite incredible risks, women continued to bear children, support each other, and carry forward knowledge through generations. The 19th century laid the groundwork for the modern maternal health reforms that would follow in the 20th century.

Understanding this history not only honors the resilience of those women but also reminds us of how far we’ve come—and how far we still must go—in ensuring safe, equitable care for all mothers.