“Blades and Glory: Henry VIII’s Masters of Defence and the Art of 16th-Century Swordplay”

Introduction: When Swordsmanship Was a National Sport

In 16th-century England, long before boxing clubs and Olympic fencing, there existed a vibrant and highly respected martial art: sword fighting. At the height of this culture stood the Masters of Defence, elite swordsmen who trained and dueled under royal patronage—particularly during the reign of Henry VIII. In Tudor England, fencing wasn’t just combat—it was theatre, sport, and status.

This article delves into the thrilling world of Tudor swordplay, exploring how it evolved, who its masters were, and how it shaped both martial tradition and royal identity.

1. The Rise of Swordplay in Renaissance England

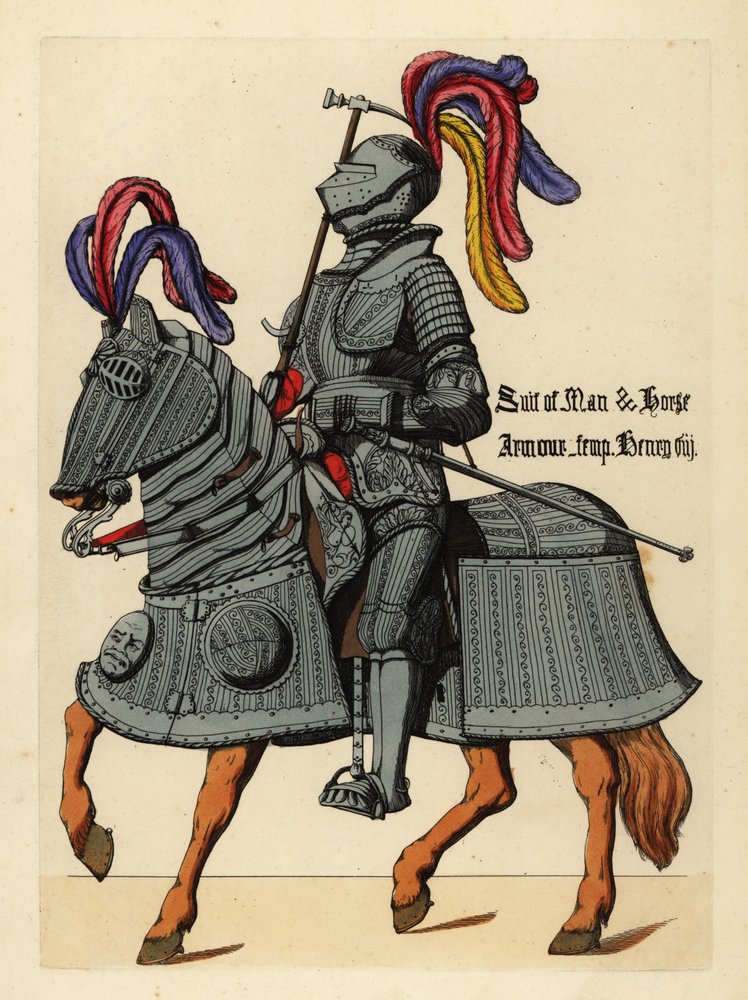

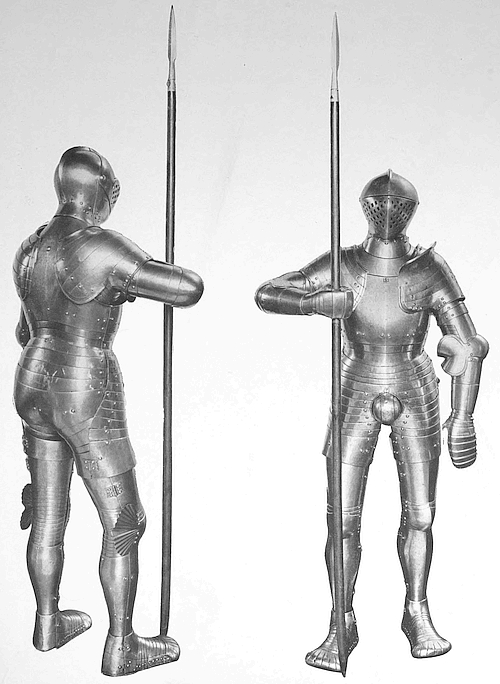

The 16th century marked a period of revival and innovation in martial arts. With the decline of armored knights and the rise of urban life, civilian swordsmanship gained prominence.

- The Renaissance brought a rediscovery of classical fighting techniques and the birth of fencing manuals.

- In cities like London, sword masters became highly regarded professionals, often running their own schools.

- Henry VIII, a sportsman and warrior-king, encouraged swordplay as part of knightly and courtly training.

2. The Masters of Defence: England’s First Martial Guild

In 1540, Henry VIII officially chartered the Company of the Masters of Defence, a royal guild of fencing instructors.

- It functioned like a regulated fraternity for swordsmen, similar to trade guilds.

- To become a Master, one had to demonstrate skill in several weapons, including:

- Longsword

- Backsword

- Two-handed sword

- Staff

- Dagger

- Examinations included public bouts, where candidates proved their worth before judges and crowds.

This guild helped standardize instruction and reduce fatal street duels by promoting regulated combat.

3. Swordplay as Entertainment: Public Bouts and Prizefights

Public fencing displays, or “playing at the prize,” were widely attended events in London and beyond.

- They blended combat with performance, featuring stylized challenges, formal declarations, and theatrical flair.

- Fighters wore color-coded sashes: a tradition passed from apprentice to provost to master.

- Though serious injuries occurred, these events were considered honorable contests, often hosted in taverns, arenas, or even at court.

Fencing was one of the few public spectacles where skill, not birth, determined respect.

4. Henry VIII: Royal Patron and Practitioner

Henry VIII was no passive observer. He was an avid swordsman, known for engaging in sparring sessions with court favorites.

- His interest helped elevate fencing to a respected courtly pursuit.

- He also introduced continental influences, particularly from Italy and Spain, which had flourishing fencing schools.

- The king’s support helped institutionalize fencing within military and noble training.

5. Weapons of the Time: From War to Duels

The 16th century saw a wide variety of weapons in use:

- Rapiers (introduced later in the century) for thrusting duels.

- Cut-and-thrust swords for both military and civilian use.

- Parrying daggers, bucklers, and staffs as common side weapons.

Swordsmanship evolved as armor declined, shifting focus from brute strength to agility, timing, and precision.

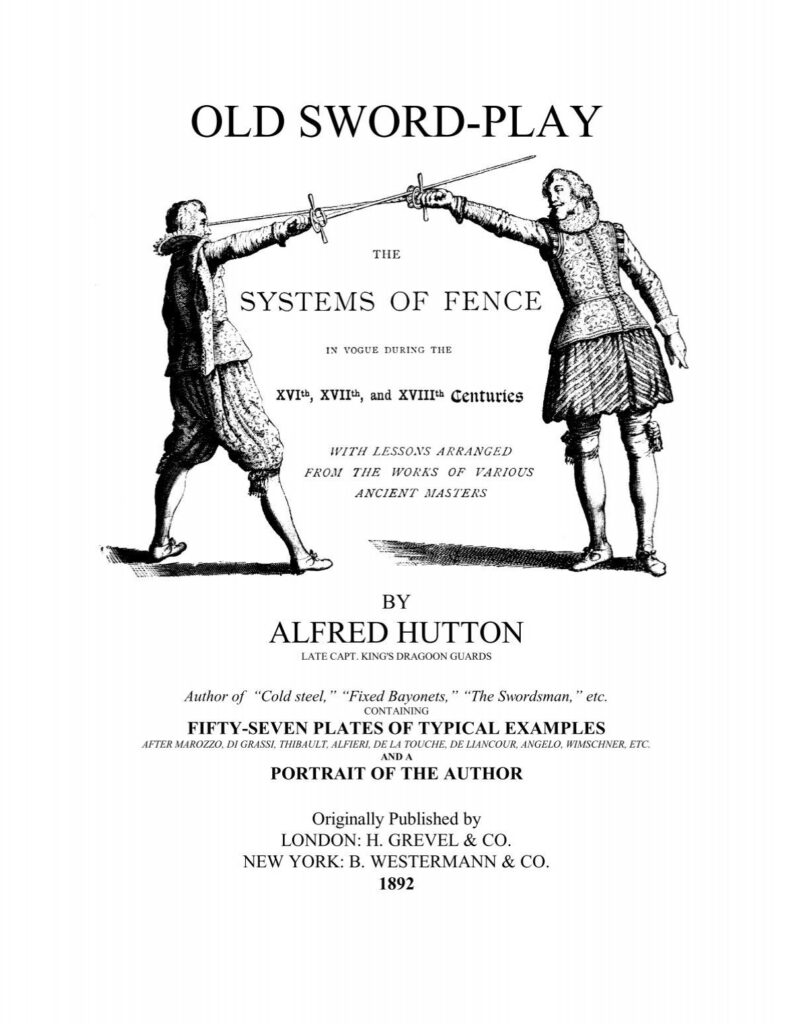

6. Manuals and Masters: Preserving the Art

English fencing masters contributed to a growing library of combat treatises, offering insight into their techniques and philosophies.

- Figures like George Silver (early 17th century) famously criticized foreign styles, championing English methods.

- Manuals covered:

- Stances

- Target zones

- Psychological tactics

- Ethics of combat

These writings bridged martial skill with scholarly respectability.

7. Decline and Legacy

By the end of the 16th century, swordplay began to evolve further:

- The rapier’s popularity ushered in a more dueling-based culture, with emphasis on honor rather than training.

- Firearms reduced the practical need for swords in warfare.

- The Masters of Defence gradually declined in influence but left behind a robust martial tradition.

Today, the legacy of Tudor swordsmanship is preserved through Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) and reenactment groups.

Conclusion: The Blade That Defined a Culture

For Tudor England, swordplay was more than combat—it was a discipline, a spectacle, and a mirror of society. Under the reign of Henry VIII, fencing flourished as both art and sport. The Masters of Defence stood as guardians of a martial tradition that blended technique, pageantry, and honor—setting the stage for centuries of European sword culture.