Matricide and Madness: Why Emperor Nero Killed His Own Mother

Introduction: A Dark Chapter in Imperial Rome

In the annals of ancient Roman history, few names provoke as much intrigue and horror as Emperor Nero. Known for extravagance, cruelty, and artistic ambition, Nero’s reign (54–68 CE) was riddled with scandal—but none more shocking than his murder of his own mother, Agrippina the Younger. While Roman emperors were no strangers to ruthless politics, Nero’s matricide stands out not just for its brutality, but for the deep psychological and political entanglements behind it.

This article unravels the tangled web of power, paranoia, and ambition that led to one of the most chilling crimes in imperial history.

1. The Woman Behind the Throne: Agrippina the Younger

Before Nero ever wore the purple, Agrippina the Younger was one of Rome’s most formidable women. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, she was:

- The daughter of Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder

- The sister of Emperor Caligula

- The niece and fourth wife of Emperor Claudius

- And eventually, the mother of Nero

Brilliant, politically savvy, and ruthlessly ambitious, Agrippina maneuvered her way through court intrigue to place her son on the throne after she allegedly poisoned Claudius in 54 CE. At first, she ruled alongside him, controlling much of Rome’s administration.

2. Nero’s Rise: From Puppet to Emperor

Nero became emperor at just 16, with Agrippina acting as regent and power broker. In the early years:

- Agrippina’s image appeared on coins beside Nero’s.

- She sat in on Senate meetings—a shocking breach of Roman norms.

- She influenced Nero’s decisions through her political alliances and manipulations.

However, Nero soon grew resentful of his mother’s domination. With his popularity rising, and under the influence of his advisor Seneca and the Praetorian prefect Burrus, Nero began to assert his independence.

3. Breaking the Bond: Tensions Mount

As Nero matured, his relationship with Agrippina deteriorated:

- She opposed his affair with the freedwoman Acte, viewing it as beneath imperial dignity.

- She grew suspicious of his increasing autonomy and tried to promote Britannicus, Claudius’ biological son, as a rival heir—until Britannicus mysteriously died.

- Nero, increasingly influenced by hedonism, flattery, and paranoia, saw Agrippina as a threat to his rule.

By 59 CE, the young emperor decided that to secure his throne, his mother had to die.

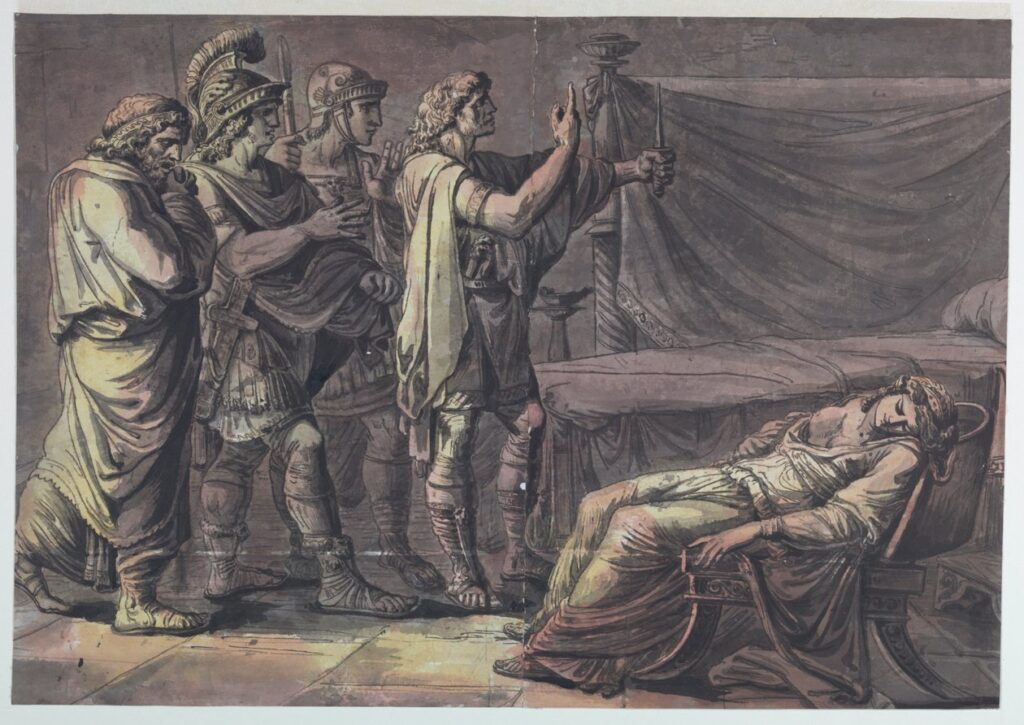

4. The Failed Assassinations and Final Blow

Killing the emperor’s mother wasn’t politically simple. Nero tried multiple elaborate assassination attempts:

- Poison was tried but failed—Agrippina, familiar with intrigue, had trained herself with antidotes.

- A collapsing ceiling was arranged but missed her.

- A booby-trapped boat was designed to sink with her onboard, but she swam to safety.

Finally, frustrated and exposed, Nero sent assassins to stab her in her villa. According to legend, Agrippina’s last words were, “Strike the womb that bore him.”

5. Aftermath: A Legacy of Blood and Infamy

Although Nero publicly claimed her death was a suicide, few were fooled. The murder horrified Rome:

- Public sympathy turned against Nero.

- He became increasingly erratic and despotic.

- His guilt reportedly haunted him—hallucinations and paranoia plagued the rest of his reign.

Her death marked the beginning of a bloody spiral. Nero would go on to kill his wife Octavia, his advisor Seneca, and many senators and nobles.

By 68 CE, Nero’s tyranny led to rebellion. Declared an enemy of the state, he died by suicide—the last emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

6. Why Did He Do It? Motive, Power, and Fear

Nero’s decision was not merely personal. It reflected deeper forces at play:

- Fear of being overthrown by his own mother

- A desire to shed her control and assert true power

- The Roman imperial model, where ruthlessness was often seen as strength

- The influence of courtiers urging him toward total control and god-like status

Nero’s world was one where familial bonds meant little against the weight of absolute rule.

Conclusion: A Crime That Defined an Emperor

The murder of Agrippina remains one of the most infamous acts in ancient history. It marked Nero’s transformation from a manipulated youth to a tyrant defined by paranoia and theatrical violence. More than just a twisted act of matricide, it symbolizes the corrosive nature of unchecked power—a mother who birthed an emperor, only to fall victim to the very monster she created.