The Intelligence of Earthworms: Uncovering the Surprising Minds Beneath the Soil

Often dismissed as simple, slimy garden dwellers, earthworms have long been overlooked in discussions of animal intelligence. Yet, beneath the soil lies a fascinating and surprisingly complex world. Scientists are beginning to uncover evidence that these invertebrates may possess a form of intelligence—not in the human sense, but in ways that challenge our assumptions about brain size, behavior, and cognition.

This article delves into the biology, neurology, and behavioral patterns of earthworms to explore just how “intelligent” they truly are—and what that might mean for our understanding of life beneath our feet.

1. A Brief Overview of Earthworms

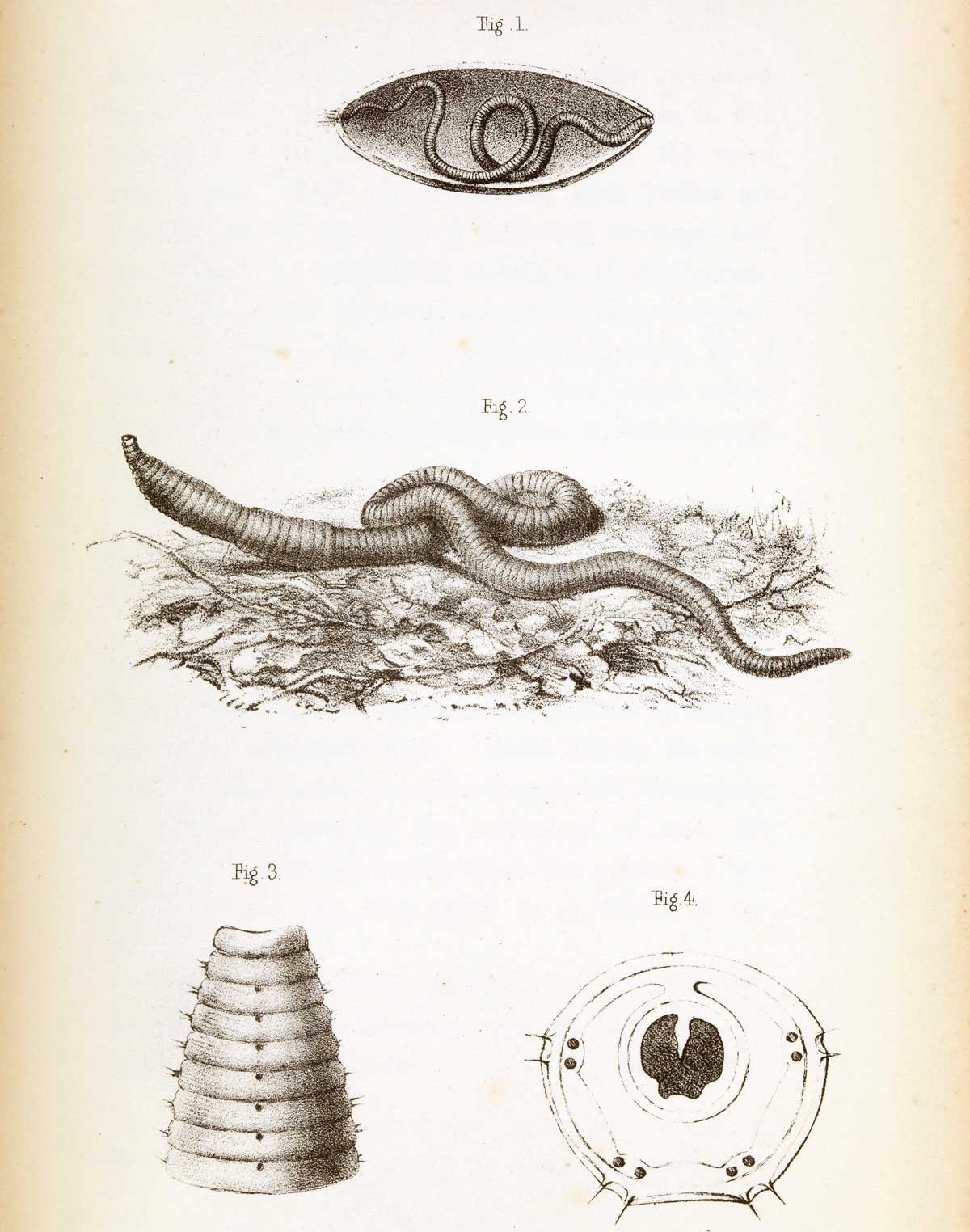

Earthworms belong to the class Oligochaeta within the phylum Annelida. With over 7,000 known species worldwide, they play a crucial ecological role by aerating soil, breaking down organic matter, and facilitating nutrient cycling.

Charles Darwin famously spent the last years of his life studying earthworms and declared in 1881 that they were among the most important animals for agriculture and soil health. His book, The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms, was a bestseller in its time.

2. Do Earthworms Have Brains?

Technically, earthworms do have a brain, albeit a simple one. It’s composed of a pair of cerebral ganglia located above the pharynx. These ganglia are connected to a nerve cord that runs the length of their body.

Though primitive compared to mammals, this nervous system allows earthworms to:

- Respond to light, touch, vibration, and chemical cues

- Coordinate movement through muscle contractions

- Make basic behavioral decisions (such as retreating from danger or avoiding noxious environments)

3. Sensory Perception and Learning

Earthworms have no eyes, but they are highly sensitive to light. They rely on photoreceptor cells in their skin to detect changes in brightness and will quickly burrow if exposed to sunlight—a vital survival mechanism since UV light can be lethal to them.

Moreover, research has demonstrated simple learning behaviors in earthworms:

- In classical conditioning experiments, earthworms can learn to associate a mild electric shock with certain conditions, avoiding them after repeated exposure.

- In maze experiments, they have shown an ability to navigate toward a goal, such as a moist or food-rich environment, and to retain information about the layout for short periods.

While this doesn’t qualify as high-level cognition, it suggests associative learning and memory, key components of intelligence.

4. Social and Environmental Intelligence

Though not social in the way ants or bees are, earthworms interact with each other through chemical signaling, especially during mating. Some studies suggest that they adjust their burrowing behavior based on the density of other worms nearby, potentially to avoid competition or overexploitation of resources.

Earthworms also display environmental intelligence. They can:

- Choose soil types that offer the best conditions for respiration and feeding

- Avoid harmful substances like salt, heavy metals, or pesticides

- Create complex burrow networks that optimize oxygen flow and waste management

These decisions require information processing, even without a centralized brain structure like that of higher animals.

5. The Role of Earthworms in Ecology

Whether or not we consider them “intelligent,” earthworms are undeniably ecosystem engineers. Their burrowing:

- Increases soil aeration

- Promotes root growth

- Enhances water infiltration

- Stimulates microbial activity

Some researchers argue that their ability to sense environmental quality and modify their surroundings amounts to a form of collective intelligence, influencing broader ecosystem dynamics.

6. Philosophical and Scientific Implications

The question of earthworm intelligence opens up broader debates in animal cognition:

- What counts as intelligence?

- Can intelligence exist without a complex brain?

- How do non-human ways of sensing and interacting shape different types of intelligence?

Increasingly, scientists are moving away from anthropocentric models that view intelligence solely in terms of language, tool use, or problem-solving. Earthworms may never build machines or paint art, but they adapt, learn, and influence their environment in ways that are impressively efficient and evolutionarily successful.

Conclusion: The Thinking Soil Beneath Us

The idea of earthworms as intelligent beings may seem odd at first glance, but science encourages us to look closer—and deeper. These invertebrates exhibit behaviors that meet many definitions of basic intelligence: perception, learning, memory, and decision-making.

Darwin may have been right to honor their role in shaping the world. As we uncover more about soil ecosystems, we may also discover that intelligence is not a hierarchy—but a spectrum, one that includes even the humblest creatures.