“Tilled to Transformed: Agriculture in the British Industrial Revolution”

Introduction: More Than Just Factories

When people think of the British Industrial Revolution, visions of smoky factories, steam engines, and crowded cities come to mind. However, the story of this transformative era is incomplete without acknowledging the quiet yet foundational revolution in agriculture that unfolded alongside the industrial one. The Agricultural Revolution in Britain provided the food, labor force, raw materials, and capital that fueled industrial growth. Without changes in farming, the Industrial Revolution may never have taken root.

The Agricultural Revolution: Setting the Stage

The Agricultural Revolution refers to a period (roughly from the late 17th to mid-19th centuries) when farming practices in Britain experienced profound transformation. These innovations preceded and overlapped with the Industrial Revolution, laying the economic groundwork.

Key elements of this agricultural shift included:

- Enclosure Movement: Common lands were consolidated into private farms, boosting efficiency and productivity, though often displacing smallholders and tenant farmers.

- Crop Rotation: The traditional three-field system was replaced with the more efficient four-course crop rotation (wheat, turnips, barley, clover), improving soil fertility and yields.

- Selective Breeding: Livestock breeding became more scientific under figures like Robert Bakewell, resulting in larger and more productive animals.

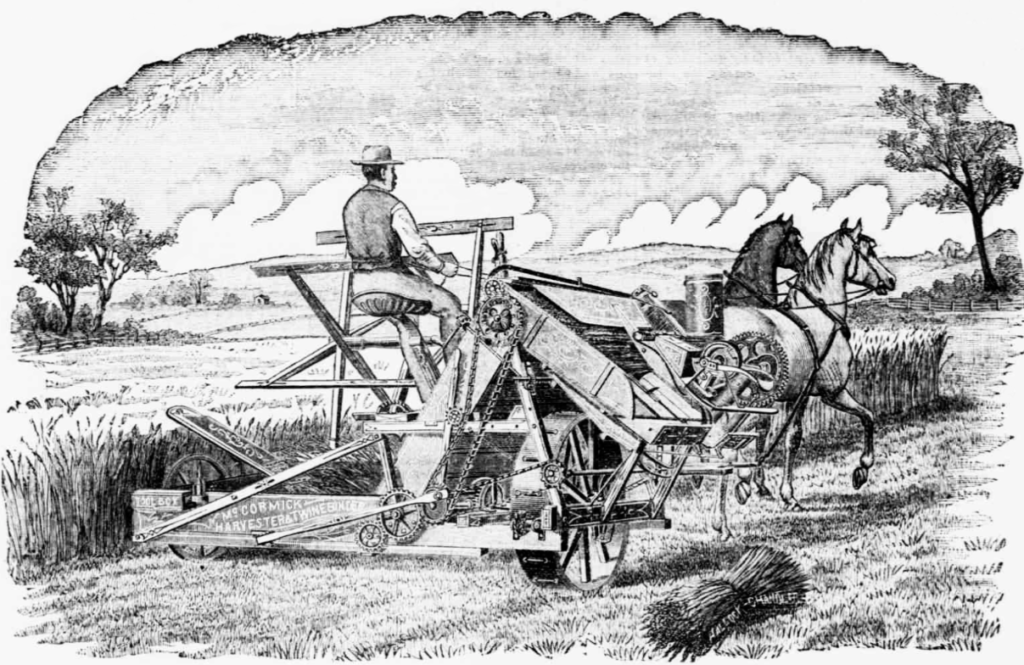

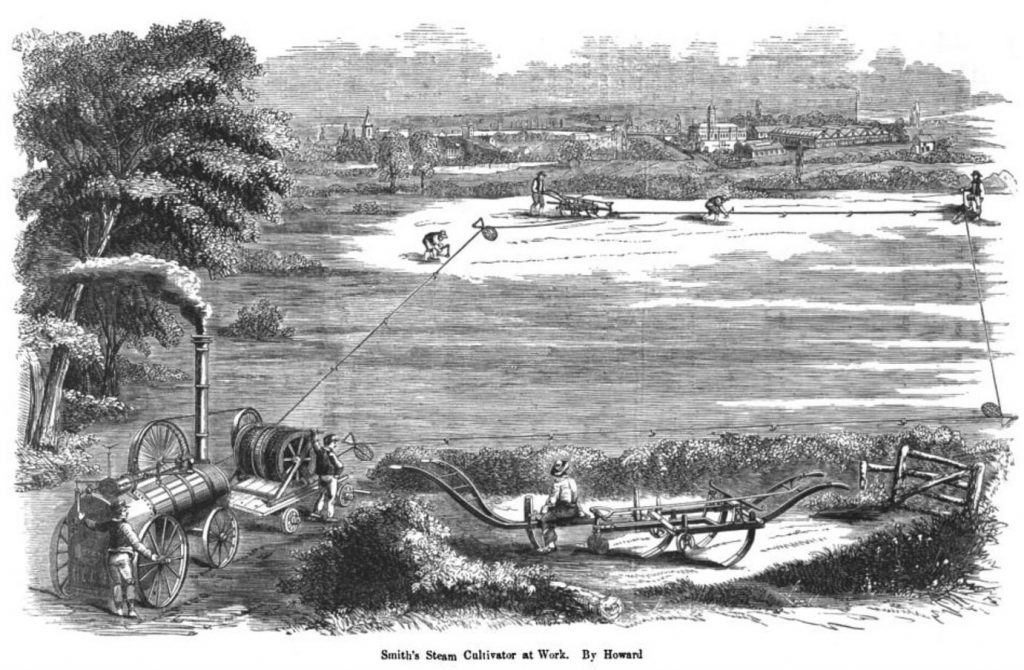

- New Tools & Mechanization: Inventions such as Jethro Tull’s seed drill mechanized planting, while the horse hoe improved weeding.

- Scientific Farming: Increased use of fertilizers, soil management, and experimentation laid the groundwork for modern agricultural science.

How Agriculture Fueled Industry

- Feeding the Population

Agricultural efficiency meant more food with fewer workers, leading to population growth. A well-fed workforce was essential to sustaining labor in growing urban centers and factories. - Labor Supply for Industry

As enclosure and mechanization reduced the need for rural labor, displaced agricultural workers migrated to towns, forming the backbone of the industrial working class. - Raw Materials for Industry

Agriculture provided key inputs for early industry, particularly:- Wool and later cotton processing

- Flax for linen

- Animal hides for leather

- Food production to support a growing non-farming population

- Capital Investment

Profits from agriculture — especially among wealthy landowners — were reinvested into industrial ventures, fueling factory construction, railways, and canals.

Rural Transformations: Winners and Losers

While agricultural advances improved productivity, they also led to profound social and economic disruptions:

- The Enclosure Movement, while boosting production, stripped communal rights from many peasants, leading to rural poverty and forced migration.

- Tenant farmers saw some benefits through higher yields and profits, but smallholders were often marginalized.

- The rural elite — those who owned large estates — became wealthier and more politically powerful.

- Women and children in rural areas faced limited opportunities, often forced into domestic or factory work as farms modernized.

Urban vs. Rural: A New Divide

As industry blossomed, so too did the divide between city and countryside. Agriculture became increasingly specialized and commercialized, while cities became crowded hubs of manufacturing, trade, and service economies. This shift would have lasting consequences on British society:

- Cities became centers of political power and innovation.

- Rural areas, though vital, were increasingly viewed as secondary to industrial progress.

- The romanticization of the countryside — as seen in poetry and art — was partly a reaction to its perceived decline in cultural centrality.

Technological Overlap: Agriculture and Industry

The Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions were not separate phenomena. They shared technologies, people, and ideas:

- Steam engines and mechanical threshers began to appear on farms.

- Iron tools, railways, and canals made farming and distribution more efficient.

- Agricultural scientists and industrialists often cross-pollinated ideas — both literally and figuratively.

Long-Term Impacts on British Agriculture

By the mid-19th century, British agriculture had transformed into a highly productive, commercially-oriented system, setting a model for other industrializing nations.

- Productivity per acre and per worker rose sharply.

- Britain became capable of feeding a vast urban population, at least until the later pressures of population growth and urban sprawl.

- The importation of cheap food during the late 19th century (e.g., from America) would eventually challenge the British agricultural sector, but its foundational role in industrialization remained unquestionable.

Conclusion: The Roots of Industrial Power

The British Industrial Revolution is often told through the clanging of machines and the rise of cities, but it was built on the quiet transformation of the fields. The Agricultural Revolution did not just feed the factories — it created the conditions in which they could flourish. Without fertile farms, innovative farmers, and the wealth of the landed elite, the great industrial leap might have stalled before it began. In many ways, the plow paved the way for the piston.