“Wounded Knee Massacre: The Tragic End of the Indian Wars”

The Wounded Knee Massacre, which occurred on December 29, 1890, remains one of the darkest and most tragic episodes in United States history. It marked the brutal culmination of decades of broken treaties, forced relocations, and military aggression toward Indigenous peoples. Taking place on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, the massacre led to the deaths of more than 250 Lakota Sioux men, women, and children—many of whom were unarmed. What began as a disarmament operation quickly devolved into a chaotic and bloody slaughter, ending the era of armed Native resistance in the American West.

Historical Background: The Ghost Dance Movement and U.S. Fear

In the late 1880s, the Ghost Dance religion, founded by the Paiute prophet Wovoka, gained traction among various Native American tribes, especially the Lakota. The movement preached nonviolence and spiritual renewal through dance and prayer, promising a return to ancestral ways and the disappearance of white colonizers.

However, U.S. officials misinterpreted the Ghost Dance as a call to war. Fear and misunderstanding among settlers and the military rapidly escalated tensions, especially on the Pine Ridge and Standing Rock reservations, where many Lakota were suffering from starvation and broken promises by the U.S. government.

Prelude to the Massacre: Sitting Bull’s Death and Lakota Flight

In December 1890, the revered Lakota leader Sitting Bull was killed during an attempted arrest by Indian police. His death further inflamed tensions. Fearing for their safety, a group of Lakota, led by Chief Spotted Elk (also known as Big Foot), began moving south toward Pine Ridge to seek refuge.

They were intercepted by the U.S. 7th Cavalry, the same regiment once commanded by George Armstrong Custer, near Wounded Knee Creek. Though Spotted Elk was ill and flying a white flag, the cavalry took the group into custody and set up camp around them.

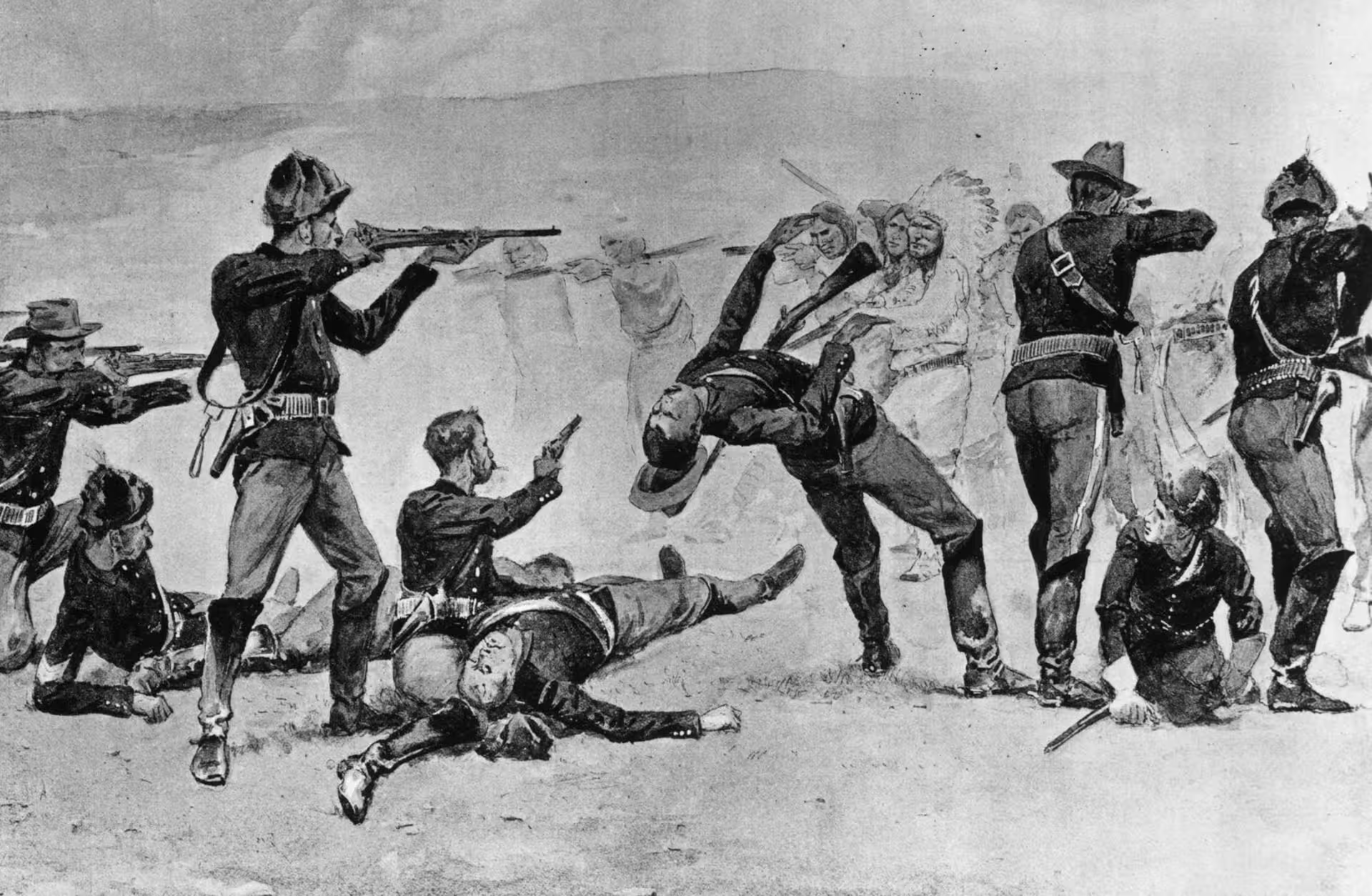

The Massacre Unfolds

On the morning of December 29, soldiers attempted to disarm the Lakota, claiming they had orders to do so. As they searched the camp, a struggle ensued—possibly triggered by a deaf Lakota man, Black Coyote, who didn’t understand the command to give up his rifle.

A shot rang out, and chaos erupted.

- The U.S. troops opened fire with rifles and Hotchkiss machine guns, even targeting those who were running away.

- More than 250 Lakota were killed, including men, women, and children.

- Around 25 U.S. soldiers died, many likely from friendly fire in the confusion.

Aftermath and Impact

The bodies of the dead Lakota were left frozen in the snow for days before being buried in a mass grave. Survivors told horrifying tales of indiscriminate killing and violence against non-combatants. Despite the scale of the tragedy, 20 Medals of Honor were awarded to U.S. soldiers who participated in the massacre—a decision still heavily criticized and protested today.

The Wounded Knee Massacre is considered:

- The final major conflict of the Indian Wars.

- A symbol of the oppression and genocide faced by Native Americans.

- A key moment that sparked long-term Indigenous resistance and advocacy for justice.

Legacy and Modern Reassessment

The massacre was largely forgotten by mainstream America for much of the 20th century. However, Native communities never let the memory fade. In 1973, the American Indian Movement (AIM) staged a 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee, demanding justice for Native peoples and drawing attention to broken treaties and systemic neglect.

In recent decades, historians, Indigenous leaders, and activists have worked to reframe Wounded Knee as a massacre—not a battle—and push for:

- Rescinding the Medals of Honor given to soldiers.

- Official apologies and reparations.

- Education and remembrance through public memorials and school curricula.

Conclusion: Wounded Knee in Historical Memory

The Wounded Knee Massacre stands as a stark reminder of the devastating cost of colonization, racism, and militarism. It marked the end of an era in U.S.-Native relations but sparked a new chapter of Indigenous advocacy and resistance.

Today, Wounded Knee is a sacred site of mourning and memory, a place that calls on all Americans to confront their past and strive for a more just and truthful future. Its legacy is not only a story of loss, but of resilience, survival, and the enduring fight for Indigenous sovereignty.